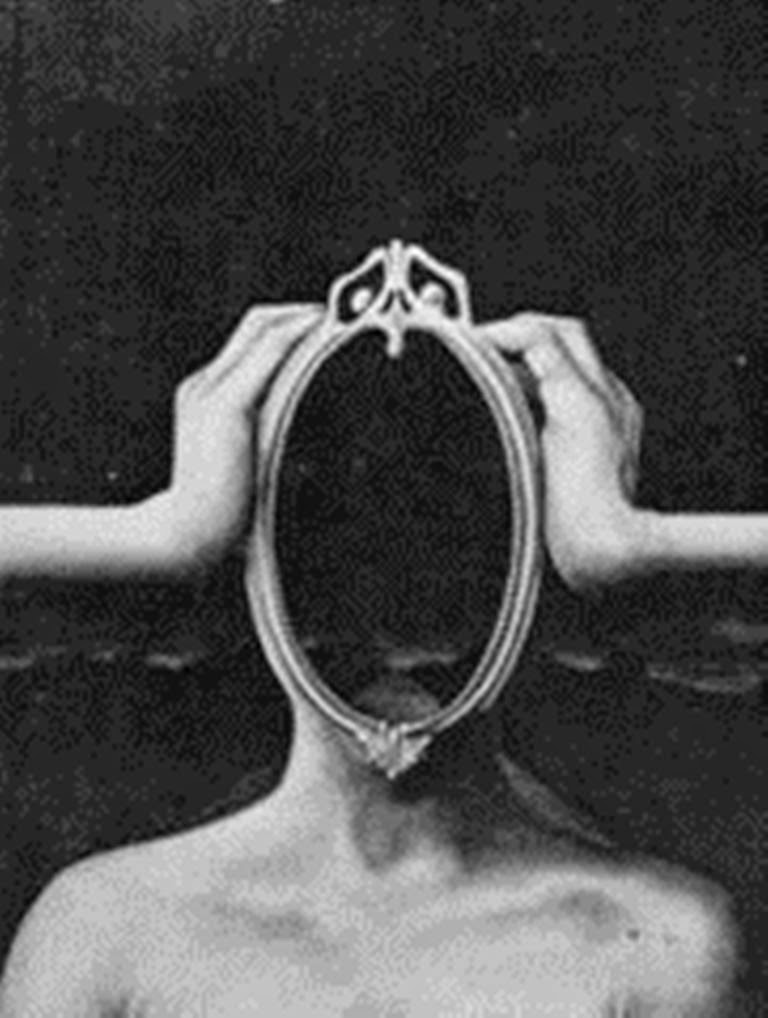

The tragic man

“In

this world only play, play as artists and children engage in it, exhibits

coming-to-be and passing away, structuring and destroying... And as children

and artists play, so plays the ever living fire. It constructs and destroys,

all in innocence... Transforming itself into water and earth, it builds towers

of sand like a child at the seashore, piles them up and tramples them down...

The ever self-renewing impulse to play calls new worlds into being. The child

throws its toys away from time to time - and starts again in innocent caprice.

But when it does build, it combines and joins and forms its structures regularly,

conforming to inner laws.”

(Nietzche)

In unveiling

narcissism as a powerful undercurrent of human experience, Freud pointed to the

similarities among the megalomania of the schizophrenic, the magical thinking

of "primitive" (non-Western) people, the blind infatuation of the

lover, and the "childish," doting adulation of parents toward their

offspring. The common element in these states, Freud argued, is

"overvaluation"-whatever is being considered, whether in oneself or

in another, is inflated in importance, its powers exaggerated, its unique perfections

extolled. The narcissistic overvaluations of the schizophrenic, the primitive,

the lover, the parent, are all secondary derivatives of a more fundamental

narcissistic condition, Freud argued, which constitutes the earliest stage of

psychic development. Freud portrays the state of primary narcissism as one of

total omnipotence, perfection, completeness. The infant imagines himself as

constituting the entire universe, or certainly all that is good and pleasurable

in it.

Illusion as

Defense

Although the

state of primary narcissism cannot be maintained for long in a world of

inevitable frustrations and increasing parental expectations, the original

narcissistic experience, in Freud's view, is not wholly renounced. Much of

narcissistic libido is transformed into object libido, self-gratification

replaced by drive gratifications facilitated by others as libidinal objects.

Some of the original narcissism remains intact, however, and self-regard

derives from three different forms in which narcissistic libido is preserved.

Some primary

narcissism simply remains from its original state and serves, like the

protoplasmic body of the amoeba, as a never-wholly emptied pool of libidinal

resources from which pseudopodlike object libidinal cathexes are drawn. Sometimes

narcissistic libido is transferred to the sexual object; here the object is not

loved in an anaclitic way, modeled after those who provided drive

gratifications, but in an idealized, narcissistic fashion, modeled after the

inflated self-love of primary narcissism. Some narcissistic libido is set up

within the ego ideal. Self-rapture in relation to the child's true attributes

is no longer possible; but if the parents' values and expectations can be

fulfilled, wholeness and perfection are once again attainable.

The common

feature in these three vicissitudes of narcissistic libido is

"overvaluation," which Freud identifies as the "narcissistic

stigma" (1914b, p. 91). Whether the focus is actually oneself, one's

wished-for self, or the beloved, the object is granted positive qualities

beyond what is supportable by reality. Thus narcissism in Freud’s system

entails the attribution of illusory value. His metaphor of the amoeba and its

oscillatory protoplasm, now extending outward into the world, now retreating

backward into the central body, highlights the· reciprocal relationship he saw

between engagement with reality (and other people) and narcissistic illusions.

For Freud, narcissistic illusions (even when they are transferred through

idealization onto love objects), ultimately draw one away from real

involvements with others and the gratifications they provide.

Although an

explorer of the darkest, most irrational dimensions of human experience, Freud

was a supreme rationalist in his sense of social, moral, and scientific values.

Rationality, fueled by sublimation, represents the highest and most felicitous

development of the human mind. The discontents we suffer in civilization are

the necessary price of its uplifting advantages. Unless impeded by neurosis,

developmental progress is characterized by a movement from primary process to

secondary process, from the pleasure principle to the reality principle.

Psychoanalysis as a treatment facilitates this process whereby the irrational

and fantastic is brought under the sway of the rational and the real -

"where id was, there ego shall be" (1933, p. 80).

Kaplan (1985)

has described Freud's dedication to rationality in striking terms.

“If people must

suffer the loss of their infantile hopes and fantasies, then they should suffer

for the fact of this loss rather than for distortions of it in aesthetic

bonuses, the empty promises of religion, and the negligible protections of

social orders. Unremitting toil in the service of science - naked means toward

real ends - was Freud's (1930/1961) alternative in Civilization and Its

Discontents, at least for himself. Any other kind of life was ensnared by

illusion, which was but a small step up from neurosis. (pp. 290-291)

In this larger

context, Freud regarded narcissistic illusions as the inevitable residue of the

most primitive and infantile state of mind, and therefore as both unavoidable

and dangerous. Precisely because narcissism, by definition, entails illusory

overvaluation, it runs counter to reality and beckons as an ever-tempting

defensive retreat. Withdrawal from reality is always perilous, the ultimate

threat being the total loss of connection with the real world (the

schizophrenic state) and the less devastating threat posed by the vulnerable

loss of self, suffered by the unrequited lover, whose narcissism is transferred

to the beloved and never returned.

Freud's stress

on the defensive function of illusions has been largely maintained in what one

might consider the mainstream of contemporary Freudian thought, although

exactly what is being defended against varies in different accounts, depending

on the larger set of theoretical premises which shape that account. Let us

consider, as examples of the traditional approach to illusion as defense, two

of the most significant recent contributions to the literature on narcissism

from within Freudian ego psychology, those of Kernberg and Rothstein.

Although

Kernberg stresses his loyalties to Mahler, Jacobson, and the ego-psychological

tradition, his contributions draw extensively on Melanie Klein's model of

mental life, and his approach to narcissistic illusion is greatly informed by her

theories. Klein portrays the infant as beset with terrifying anxieties

involving the containment of aggression, and sees early development as a

movement from paranoid and depressive anxieties toward a more integrated and

secure sense of reality. Within Klein's vision, narcissistic illusions operate

as defenses and regressive retreats from these frightening early anxieties:

idealization is a refuge from persecutory anxiety and murderous rage toward bad

objects; grandiosity is a "manic" defense against the depressive

anxiety inherent in feeling small, helpless, and abjectly dependent upon

another. Kernberg borrows heavily from these conceptualizations.

He distinguishes

normal from pathological narcissism, defining the former (following Freud, as

amended by Hartmann, 1950, p. 127) as the libidinal investment of the self.

What Kernberg means by normal narcissism, then, is the resultant of all the

processes which bear on self-representation and self-regard. He sees

pathological narcissism as a particular dynamic mechanism which generates both

entitled grandiosity and primitive idealization. Following Klein, Kernberg

characterizes these as primitive defense mechanisms, often operating in

conjunction with other primitive defense mechanisms such as splitting, denial,

and projective identification. Narcissistic illusions are a defense erected

within the child's struggle with a "pathologically augmented development

of oral aggression" (1975, p. 234), generating paranoid and depressive

anxieties; the illusions are constructed from a pathological fusion of ideal

self, ideal object, and actual self-image.

How do

narcissistic illusions work? In Kernberg's account, the infant is overloaded

with primitive aggressive impulses, due to a "constitutionally determined

strong aggressive drive, or constitutionally determined lack of anxiety

tolerance in regard to aggressive impulses, or severe frustration in their first

year of life" (1975, p. 234). He experiences himself and, projectively,

other people as well, as essentially sadistic, and this aggressive outlook

dominates his early experience. Sticking close to Klein's account of

"envy" (1957), Kernberg portrays the narcissistically prone infant as

so frustrated and hateful as to be unable to tolerate hope, the possibility of

anyone's offering him anything pleasurable or sustaining. So little is

forthcoming, the child concludes, and with such ill will toward him, that it is

better to expect nothing, to want nothing, to spoil and devalue everything that

might be offered. Normal fantasies of self and other as ideal are fused with

the child's own realistic self-perceptions, resulting in a ‘grandiose self'

which is experienced as complete, perfect, and self-sustaining. "I am/have

everything. You are/offer nothing." This position serves as both an

expression of and a defense against explosive oral aggression, and the only

secure solution in a world experienced as treacherous and sinister. Maintenance

and protection of the grandiose self becomes the central psychodynamic motive,

resulting in a contemptuous character style and disdainful manner of relating

to others.

“A narcissistic

patient experiences his relationships with other people as being purely

exploitative, as if he were "squeezing a lemon and then dropping the

remains." People may appear to him either to have some potential food

inside, which the patient has to extract, or to be already emptied and therefore

valueless.” (1975, p. 233)

Primitive

idealization of others is also characteristic of personalities organized around

a grandiose self, according to Kernberg, but the idealization has little to do

with any real valuing of others. Rather, Kernberg's narcissistic patient

projects his own grandiose self-image onto others when it becomes impossible to

sustain within himself, and also uses idealization as a secondary defense,

along with splitting, to ward off and conceal the hateful and contemptuous

devaluation of others.

Thus,

narcissistic illusions protect the patient from the dreadful state in which he

spent much of the first several years of life, depending on others for

protection and care, yet perpetually dissatisfied, victimized, and enraged. The

establishment of the grandiose self removes the patient from the multifaceted

psychic pain of this situation, and, once established, the grandiose self

perpetuates the devaluing assumptions about others which made its establishment

necessary in the first place. It creates a "vicious circle of

self-admiration, depreciation of others, and elimination of all actual

dependency. The greatest fear of these patients is to be dependent on anybody

else, because to depend means to hate, envy, and expose themselves to the

danger of being exploited, mistreated, and frustrated" (Kernberg, 1975, p.

235).

Narcissistic

illusions have a perniciously sabotaging effect on psychoanalytic treatment.

Based on the illusions of self-sufficiency and perfection of the grandiose

self, they undercut the very basis on which the psychoanalytic process rests,

the presumption that the analysand might gain something meaningful from someone

else (in this case the analyst). Despite what might be considerable psychological

suffering and a genuine interest in treatment, the analysand whose character is

organized around a grandiose self cannot allow the analyst to become important enough

to him to really help him. The analyst and his interpretations must be

continually devalued, spoiled, to avoid catapulting the patient into a

condition of overpowering longing, abject dependency, and intolerable hatred

and envy.

Kernberg's

technical recommendations are wholly consistent with this psychodynamic

portrait-a methodical and persistent interpretation of the defensive function

of grandiosity and idealization as they emerge in the transference (1984, p.

197). Anything else is a waste of time, since the narcissistic illusions

systematically destroy the very ground upon which the treatment proceeds.

Unless the workings of the grandiose self are continually brought to light and

confronted, the impact of the treatment is often subtly but systematically

vitiated. "The analyst must continuously focus on the particular quality

of the transference in these cases and consistently counteract the patient's

efforts toward omnipotent control and devaluation" (1975, p. 246). This

traditional emphasis on aggressive interpretation of narcissistic phenomena

derives from and is wholly consistent with Freud's early view of

"narcissistic neurosis" as unanalyzable and narcissistic defenses as

generating the most recalcitrant resistances to the analytic process. (See, for

example, Abraham, 1919.)

Rothstein (1984)

has presented a rich amalgam of dynamic formulations which he portrays as an

"evolutionary" extension of Freud's structural model (from which he

has deleted virtually all energic considerations). The result is a

psychodynamic account which stresses conflict among various relational motives

and puts particular stress on the importance of the actual relationship to

significant others. The most pervasive influence on Rothstein's perspective,

particularly with regard to more severe disorders, is Mahler's depiction of the

process of separation-individuation from an original symbiotic matrix. Rothstein's

approach to narcissism is a blend of Freud's original formulations and Mahler's

more contemporary view of the child's struggle for relational autonomy.

Rothstein

distinguishes Freud's phenomenological portrayal of narcissism as a "felt

quality of perfection" from his metapsychological treatment of narcissism

(as the libidinal cathexis of the ego). He adds symbiosis to Freud's account of

primary narcissism and sees narcissistic illusions as based developmentally on

pre individuated experiences of a perfect self fused with a perfect object. The

loss of this original state of perfection is a severe narcissistic blow, an

inevitable developmental insult which is traversed only by reinstating the lost

narcissistic perfection in the ego ideal. By identifying with the

narcissistically tinged images of the ego ideal, the child softens the

otherwise unbearable pain of separation. "Narcissistically invested

identification is the sole condition under which the id can give up its objects

and is a fundamental concomitant of primary separation-individuation. The

pursuit of narcissistic perfection in one form or another is a defensive

distortion that is a ubiquitous characteristic of the ego" (Rothstein,

1983, p. 99).

Thus, like

Freud, Rothstein sees some residues of primary narcissism as inevitable,

reestablished in the ego ideal. For Rothstein, with his Mahlerian perspective,

the loss of infantile narcissism has an additional poignancy, since it

represents not just the loss of grandeur and perfection, but the loss of the

original symbiotic state. Accordingly, narcissistic illusions operate as

defensive retreats not only from disappointments in reality in general, but

also from anxiety and dread connected with separation. He holds that

"narcissistic perfection is a defensive distortion of reality" (p.

98). Like many defenses within the ego-psychological model, narcissism itself

is neither healthy nor pathological; some defenses are necessary and serve

adaptive functions within the psychic economy. Although a total relinquishment

of narcissistic illusions is impossible, it is the goal of analysis, in

Rothstein's view, to identify and work through the salient narcissistic

investments.

Although

proceeding from a very different set of basic assumptions concerning the

motivational and structural underpinnings of emotional life, the major

theorists within the interpersonal tradition have taken an approach to the

clinical phenomenon of illusions, the implications of which are quite similar

to the mainstream Freudian approach from Freud to Kernberg to Rothstein. Sullivan

sees idealization as a dangerous, self-depleting security operation and stresses

the "cost" to the patient of "thinking the doctor is wonderful"

(White, 1952, p. 134). He recommends challenging the patient's assumptions that

the analyst is so different from other people, often a product ofinexperience

in taking risks with others, and sees extended periods ofidealization as

reflecting a kind of acting out of countertransference. "The effective

restriction of idealization is dependent on the physician's own freedom from

personality warp. In so far as he is capable of real intimacy in the situation

with the patient, to that extent he can inhibit idealization... The measure

of this capacity [is] intuited or empathized by any patient" (Sullivan,

1972, p.343).

Similarly,

Sullivan regards grandiosity as a dynamic for covering over feelings of

insecurity through "invidious comparison" between oneself and others,

“an accelerating spiral of desperate attempts to prop up a steadily undermined security,

with the result that the patient is more and more detested and avoided… If the

patient will be alert to how small he feels with anybody who seems to be at all

contented or successful in any respect, then he may not have need for this

hateful superiority-which is hateful in part because he hates himself so much,

being unable to be what he claims to be.” (quoted in White, 1952, p. 139)

Although

Sullivan does not develop an explicit technical procedure for the handling of

illusions, one gets the clear impression throughout his writings that the

analyst is in no way helpful by failing to address the patient's overvaluation

of either himself or the analyst. Both kinds of illusions are seen as

self-sabotaging devices propping up a shaky sense of self-esteem, operating as

an obstacle to the development of the analysand's own resources and

self-respect.

Fromm takes an

even dimmer view of the place of illusion in emotional life. He sees

psychodynamics in the general context of certain inescapable realities of the

human condition, among which are finitude and separateness. To this condition

two kinds of responses are possible: progressive, productive responses which

accept the existential realities and create meaningful ties to others; and regressive,

destructive responses, based on a self-deluding denial of the realities of the

human condition. The overvaluing of illusions concerning the self or others

from whom one derives some compensatory reassurance are regressive

self-deceptions from Fromm's perspective and must be dealt with as such. In

fact, at several points Fromm accuses Sullivan, in his emphasis on protecting

the analysand's need for security, of being in effect soft on illusions.

Anything short of a continual interpretive challenge to the analysand's

overvaluing illusions concerning both himself and the analyst would be an

expression of countertransferential contempt on the analyst's part, a

disrespectful collusion in the analysand's flight from reality and meaning.

Thus, although deriving

from very different psychodynamic traditions and assumptions, the major lines

of theorizing within orthodox theory, Freudian ego psychology, and

interpersonal theory all converge in an essentially similar technical approach

to the clinical phenomenon of narcissistic illusions. The latter are viewed as

regressive defenses against frustration, separation, aggression, dependence,

and despair. Transferential illusions concerning either the self or the analyst

must be interpreted, their unreality pointed out, and their defensive purpose

defined.

Illusion as

Creativity

In recent years

there has emerged an alternative view of infantile mental states and the

narcissistic illusions which are thought to derive from them. This approach is

closely connected with the developmental-arrest model of psychopathology and

the therapeutic action of psychoanalytic treatment. The most important

contributors to this very different perspective have been Winnicott and Kohut,

each of whom in his own distinct fashion regards infantile narcissism and

subsequent narcissistic illusions in later life as the core of the self and the

deepest source of creativity. Here the prototypical "narcissist" is

not the child, madman, or savage, but the creative artist, drawing for

inspiration on overvaluing illusions.

Although

Winnicott did not often write about narcissism per se, his entire opus revolves

around the issue which we have seen is central to that domain: the relationship

between illusion and reality, between the self and the outside world. For

Winnicott, the key process in early development is the establishment of a sense

of the self experienced as real. For this to happen, the child requires a very

particular sort of relationship with his or her providers, the most

distinguishing feature of which is, ironically, that the child must not know of

the existence of the relationship, must not know that it is being provided at

all.

The essential

feature ofthe necessary "facilitating" environment provided by the

mother is her effort to shape the environment around the child's spontaneously

arising wishes, to read the child's needs and provide for them. The mother's

actualization of the infant's desires makes it possible for the latter to

assume that his wishes actually create the objects of his desire - that the

breast, in effect his entire world, is the product of his creation. In fact,

Winnicott characterizes the child's experience, made possible by the mother's

perfect accommodation to his wishes, as the "moment of illusion." The

virtual invisibility of Winnicott's "good enough mother" allows the

infant a developmentally crucial immersion in an illusory, megalomaniacal,

solipsistic state of "subjective omnipotence."

Eventually the

child learns to live in objective reality (introduced largely through the

mother's incremental failure to accommodate herself to the child's wishes) as

it becomes clear that objects and people have their own independent existence

and are only minimally under the child's control. The distinguishing

characteristic of the terrain between the original subjective omnipotence and

the eventual objective reality, transitional experiencing, is an ambiguity

about the status of the other. Is the transitional object (the traditional

teddy bear, for example) a creation of the child, in some special relation to the

child, under his or her control, or is it simply an object within the world of

mundane objects, subject to being lost, damaged, discarded, washed? The

good-enough parent of the transitional stage allows the child this ambiguity,

participating in the child's illusions like the mother whose accommodation

makes possible the earlier experience of subjective omnipotence, thereby enabling

the child to solidify a sense of self as a consistent source of spontaneous

wishes, longings, and resources.

Freud measured

mental health in terms of the capacity to love and work; Winnicott envisions

health as the capacity for play, as freedom to move back and forth between the

harsh light of objective reality and the soothing ambiguities of lofty

self-absorption and grandeur in subjective omnipotence. In fact, Winnicott

regards the reimmersion into subjective omnipotence as the ground of

creativity, in which one totally disregards external reality and develops one's

illusions to the fullest. He originally presented his view of patients with

fragmented, aborted (false) selves as a distinct diagnostic group reflecting

more severe psychopathology and, employing the developmental tilt, he placed

them developmentally as antedating oedipal neuroses. As is often the case with

theoretical innovations introduced through the establishment of a new

diagnostic category, the category spreads and the formulations take on more and

more general relevance. Thus, many varieties of psychopathology came to be viewed

by Winnicott as reflecting deficiencies in the establishment of a healthy self,

as a consequence of insufficient experience of the illusions of subjective

omnipotence and the transitional phase.

This view of the

development of the self led Winnicott to redefine both the analytic situation

and the analytic process. Whereas Freud saw the analytic situation in terms of

abstinence (instinctual wishes emerge and find no gratification), Winnicott

sees the analytic situation in terms of satisfaction, not of instinctual

impulses per se, but of crucial developmental experiences, missed parental

functions. The couch, the constancy of the sessions, the demeanor of the

analyst these become the "holding environment" which was not provided

in infancy. Freud saw the analytic process in terms of renunciation; by

bringing to light and renouncing infantile wishes and illusions, healthier and

more mature forms of libidinal organization become possible. Winnicott sees the

analytic process in terms of a kind ofrevitalization; the frozen, aborted self

is able to reawaken and begin to develop as crucial ego needs are met.

Although

Winnicott does not apply this model of treatment to the problem of narcissistic

illusions per se, its implications are clear. The patient's self has been

fractured and crushed by maternal impingement, creating the necessity for a

premature adaptation to external reality and a disconnection from one's own

subjective reality, the core of the self and the source of all potential

creativity. The analyst's task is to fan the embers, to rekindle the spark. He

must create an atmosphere as receptive as possible to the patient's

subjectivity; he must avoid challenging the patient in any way which could be

experienced as an impingement, an insistence once again on compliance with

respect to external reality. Narcissistic illusions, in Winnicott's model, are

neither defenses nor obstructions. The patient's illusions concerning both

himself and the analyst represent the growing edge of the patient's aborted

self; as good-enough mothering entails an accommodation of the world to sustain

the infant's illusions, good-enough analysis entails an accommodation of the

analytic situation to the patient's subjective reality, a "going to meet

and match the moment of hope" (1945, p. 309).

The more

explicit technical implications of this new understanding of the meaning of

narcissistic illusions were developed by Kohut, who, like Winnicott, introduced

his innovations in connection with a diagnostic category of greater severity

(narcissistic personality disorders), but who expanded those innovations into a

broad and novel theory of development, psychic structure, and motivation. In

his original 1971 presentation Kohut described two forms of transference, the

mirroring transference and the idealizing transference, which, he argued, are

very different from ordinary neurotic transferences. Here the patient is not

simply transferring infantile impulses and conflicts onto the person of the

analyst as a differentiated object. In the mirroring and idealizing

transferences, the analyst and his responses function in lieu of missing

psychic structures within the patient's own personality. In mirroring

transference the patient experiences himself in terms of overvaluing

grandiosity and requires the analyst's mirroring responses to avoid a

disintegration of self. In idealizing transference the patient experiences the

analyst in terms of overvaluing admiration and requires the analyst's allowance

of the idealization to avoid a disintegration of self.

In Kohut's

account, the appearance of narcissistic illusions within the analytic

situation-primitive grandiosity or idealization-represents the patient's

attempt to establish crucial developmental opportunities, a self-object

relationship unavailable in childhood. These phenomena represent not a

defensive retreat from reality (a la Freud, Sullivan, Rothstein, and Kernberg),

but the growing edge of an aborted developmental process which was stalled

because of parental failure to allow the child sustained experiences of

illusions of grandeur and idealization. Thus, the appearance of narcissistic

illusions within the analytic relationship constitutes a fragile opportunity

for the revitalization of the self. The illusions must be cultivated, warmly

received, and certainly not challenged, allowing a reanimation of the normal

developmental process through which the illusions will eventually be

transformed, by virtue of simple exposure to reality in an emotionally

sustaining environment, into more realistic images of self and other.

Kohut stresses

throughout that he is recommending an "empathic comprehension" of

narcissistic needs and not "playacting" or "wish

fulfillment." But empathic comprehension certainly entails a receptivity

to the narcissistic illusions and an avoidance at all costs of anything which

would challenge" them or suggest that they are unrealistic. "While it

is analytically deleterious to bring about an idealization of the analyst by

artificial devices, a spontaneously occurring therapeutic mobilization of the

idealized parent imago or of the grandiose self is indeed to be welcomed and

must not be interfered with" (1971, p. 164). Kohut sees the dangers of

interference, analogous to Winnicott's notion of impingement, as very great

indeed and warns against even "slight overobjectivity of the analyst's

attitude or a coolness in the analyst's voice; or… the tendency to be jocular

with the admiring patient or to disparage the narcissistic idealization in a

humorous and kindly way" (p. 263). Anything short of warm acceptance of

narcissistic illusions concerning both the self and the analyst-which illusions

are assumed to simply express themselves, independent of the interactional

field in which the analyst participates-runs the risk of closing off the

delicate, pristine narcissistic longings and thereby eliminating the

possibility of the reemergence of healthy self development.

There is a

striking symmetry between these two different traditions of understanding

narcissistic illusions; for each, the approach of the other borders on the

lunatic. From Kohut's point of view, the kind of methodical interpretive

approach to narcissistic transferences recommended by Kernberg is extremely

counterproductive, implying a countertransferential acting out. For Kohut,

Kernberg's stance suggests great difficulty in tolerating the position in which

the narcissistic transferences place the analyst, arousing anxiety concerning

his own grandiosity (in the idealizing transference) or envy of the patient's grandiosity

(in the mirroring transference). Thus, Atwood and Stolorow argue that the oral

rage Kernberg sees in borderline patients is actually an iatrogenic consequence

of his technical approach. Methodical interpretation of the transference is

experienced by the narcissistically vulnerable patient as an assault and

generates intense narcissistic rage, which Kernberg then regards as basic and

long-standing, requiring the very procedures which created it in the first

place. From the vantage point of self psychology, Kernberg is continually

creating the monster he is perpetually slaying.

Similarly, from

the more traditional point of view, the Winnicott-Kohut approach is an exercise

in futility. An unquestioning acceptance of the patient's illusions with the

assumption that they will eventually diminish of their own accord represents a

collusion with the patient's defenses; the analytic process is thereby subverted,

and the analyst never emerges as a figure who can meaningfully help the

patient. From the traditional vantage point, the Winnicott-Kohut approach

suggests what Loewald (1973) has termed a countertransferential

"overidentification with the patient's narcissistic needs" (p. 346).

Loewald further suggests that Kohut's avoidance of any focus on "an

affirmation of the positive and enriching aspects of limitations" of self

and others constitutes a "subtle kind of seduction of the patient"

(p. 349). As Kernberg notes, unresolved narcissistic conflicts in the analyst

"may foster excessive acceptance as well as rejection of the patient's

idealization… To accept the admiration seems to be an abandonment of a neutral

position." (1975, p. 298).

Illusion as

defense, illusion as the growing edge of the self-these two approaches derive

most broadly from larger divergent perspectives on the relation between the

individual and society that have a long history in Western culture. From one

perspective (developed to its fullest by the Enlightenment philosophers of the

eighteenth century), culture and civilization humanize the individual creature,

whose personal subjectivity is beneficially renounced in favor of the higher

objectivity and rationality of society. From the other perspective (developed

to its fullest in the Romantic movement of the nineteenth century), subjective

experience is a-higher form of reality; society threatens what is most precious

in the individual, and conventional "rationality" is portrayed as an

oppressive-repressive force.

These two

approaches to illusion have generated an exciting controversy in the analytic literature,

particularly because they are dramatically contrasting and mutually exclusive

(which is often the case with competing psychoanalytic theories in their

polarized swings of the pendulum). This controversy demonstrates dramatically

the extent to which concepts like neutrality, countertransference, and empathy

are theory bound.

It is a mistake

to regard one of these approaches as more empathic than the other. They simply

proceed (empathically) from different assumptions about the patient's

experience. Kernberg's narcissist lives in an embattled world, in which he and

all others are experienced as sadistic, self-serving, and exploitative. The

only possible security lies in a devaluation of others, disarming them of their

power to hurt him. From this perspective, an empathic response entails an

appreciation of his endangered status (see Schafer, 1983) and a delineation of

his narcissistic defenses, along with an effort to make some meaningful contact

possible. To simply accept the grandiosity would be to empathize only with the

most superficial level of the patient's defenses and not with what is presumed

to be his underlying experience.

Kohut's

narcissist, on the other hand, is a brittle creature who lives in a harsh and

continually bruising world. The only possible security lies in a splitting off

of important segments of the self (either vertically or horizontally) in an

effort to protect the deep and tender feelings connected to them, often covered

over by bravado or narcissistic rage. From this perspective, an empathic

response entails an appreciation of the continual threat of self-dissolution

and disintegration, and an encouragement of growth-enhancing illusions. To

challenge the patient's illusions would be to perpetuate the repeated traumas

of childhood. With narcissistic illusions, as with most analytic phenomena,

empathy and countertransference are in the eye of the beholder.

I strongly

suspect that the majority of analysts work in neither of these two sharply

contrasting ways, that most ofus struggle to find some midpoint, undoubtedly

reflective of our own personality and style, between challenging and accepting

narcissistic illusions. Because subtlety and tone are crucial, it is difficult

to formulate such a clinical posture in simple, schematic terms. The following

description is offered as a framework for locating such an approach conceptually

and in terms of technique, within an integrated relational perspective.

The more

traditional approach to narcissism highlights the important ways in which

narcissistic illusions are used defensively, but misses their role in health

and creativity and in consolidating certain kinds of developmentally crucial

relationships with others. The developmental arrest approach has generated a

perspective on narcissism which stresses the growth-enhancing function of

narcissistic illusions, but overlooks the extent to which they often constrict

and interfere in real engagements between the analysand and other people,

including the analyst.

It is possible

to draw upon the clinical wisdom in both these contributions by viewing

narcissistic illusions in the context oftheir interactive role in perpetuating

the analysand's relational matrix. In viewing narcissism as either only

defensive or as fundamentally growth enhancing, both traditions overemphasize

what is taken to be the inherent nature of narcissistic illusions. What has

been neglected is the key function of narcissism throughout the life cycle in

perpetuating stereotyped patterns of integrating interpersonal relationships and

fantasied ties to significant objects.

An Integrated

Relational Approach

All varieties of

narcissistic illusions are generated throughout the life cycle, from the

exuberance of the toddler to the nostalgic musings of old age: grand

estimations of one's own capacities and perfection, infatuation with the

larger-than-life qualities of others whom one loves or envies, and fantasies of

an exquisite, perfect merger with desirable or dreaded others. The

determination of emotional health as opposed to psychopathology, when it comes

to narcissistic illusions, has less to do with the actual content of the

illusions than with the attitude of the individual about that content. All of

us probably experience at various times feelings and thoughts as self-ennobling

as the most grandiose narcissist, as devoted as the most star-struck idealizer,

as fused as the most boundaryless symbiosis seeker. The problem of narcissism

concerns issues of character structure, not mental content; it is not so much

what you do·and think as your attitude toward what you do and think, how

seriously you take yourself. How can this subtle issue of attitude be

conceptualized?

Consider

Nietzsche's theory of tragedy (1872/1956). Life is lived in two fundamental

dimensions, Nietzsche suggests. On the one hand, we live in a world of

illusions, continually generating transient forms and meanings with which we

play and then quickly discard. This facet of living Nietzsche terms Apollonian,

Apollo being the god of the dream, art, and illusion. On the other hand, we are

embedded in a larger unity, a universal pool of energy from which we emerge

temporarily, articulate ourselves, and into which we once again disappear. This

facet of living Nietzsche terms Dionysian, Dionysus representing reimmersion in

this undifferentiated oneness and, in Nietzsche's system, the inevitable

undoing of all illusions, all individual existence.

Nietzsche

establishes "the tragic" as the fullest, richest model of living, and

the truly tragic represents a balance between the Apollonian and Dionysian

dimensions. The tragic man (this phrase must be disentangled from all

pejorative connotations) is one who is able to fully pursue his Apollonian

illusions and also is able to relinquish them in the face of the inevitable

realities of the human condition. The tragic man regards his life as a work of

art, to be conceived, shaped, polished, and inevitably dissolved. The

prototypical tragic activity is play, in which new forms are continually

created and demolished, in which the individuality of the player is continually

articulated, developed, and relinquished. In the passage used as the epigraph

for this chapter, Nietzsche uses the building of sandcastles as a metaphor for

the dialectic he envisions as the underlying structure of life and the essence

of the tragic.

Picture the

beach at low tide. Three different approaches are possible. The Apollonian man

builds elaborate sandcastles, throwing himself into his activity as if his

creations would last forever, totally oblivious to the incoming tide which will

demolish his productions. Here is someone who ignores reality and is therefore

continually surprised, battered, and bruised by it. The Dionysian man sees the

inevitability of the leveling tide and therefore builds no castles. His

constant preoccupation with the ephemeral nature of his life and his creations

allows him no psychic space in which to live and play. He will only build if

his productions are assured of immortality, but unlike the Apollonian man, he

suffers no delusions in this regard. Here is someone tyrannized and depleted by

reality.

The third option

is Nietzsche's tragic man, aware of the tide and the transitory nature of his

productions, yet building his sandcastles nevertheless. The inevitable

limitations of reality do not dim the passion with which he builds his castles;

in fact, the inexorable realities add a poignancy and sweetness to his passion.

The tragicomic play in which our third man builds, Nietzsche suggests, is the

richest form of life, generating the deepest meaning from the dialectical

interplay of illusion and reality.

The very word

"illusion," Loewald (1974, p. 354) reminds us, derives from the Latin

“ludere”, to play. Healthy narcissism reflects Nietzsche's subtle dialectical

balance between illusions and reality; illusions concerning oneself and others

are generated, playfully enjoyed, and relinquished in the face of disappointments.

New illusions are continually created and dissolved. Winnicott (1971) has described

the important connections between healthy illusion, play, creativity, and cultural

phenomena in general.

In pathological

narcissism, on the other hand, illusions are taken too seriously, insisted

upon. In some narcissistic disturbances, illusions are actively and consciously

maintained; reality is sacrificed in order to perpetuate an addictive devotion

to self-ennobling, idealizing, or symbiotic fictions. This is the approach of the

first man on the beach, blindly building and building. In some narcissistic

disturbances, illusions are harbored secretly or repressed; preoccupation with

the limitations and risks of reality lead to an absence of joyfulness or

liveliness - even a paralysis. Any activity is threatening because it

inevitably encounters limitations, and these are felt to be unacceptable. This

is the approach of the second man on the beach, holding out for immortality and

waiting in despair for the tide.

What is the

etiology ofsuch disturbances? What determines whether one will be able to

negotiate the delicate balance between illusions and reality in healthy

narcissism, or whether one will suffer an addictive devotion to illusions

resulting in either a removal from reality or a despair in the face of it? The

key factor resides in the interplay of illusions and reality in the

character-forming relationships with significant others. What is crucial, therefore,

is the interactive function of illusions within the analysand's relational

matrix.

The growth of the balance necessary for healthy

narcissism requires a particular sort of relationship with a parent, in which

the parent is able to comfortably experience both the child and herself in both

modes, in playful illusions of grandiosity, idealization, and fusion, and in

deflating disappointments and realistic limitations. The child naturally and

playfully generates lofty self-overvaluations, glowing overvaluations of the parent,

and boundaryless experiences of sameness and fusion. The ideal parental

response to these experiences consists in a participation coupled with the

capacity to disengage, a capacity to enjoy and play with the child's illusions,

to add illusions of his or her own, and to let the illusions go, experiencing

the child and herself in more realistic terms. Thus, the parent participates

with the child in requisite experiences characterized by shifting idealization

and aggrandizements - now the child is elevated, now the parent, now both

together. The ideal parental

response is neither a total immersion in illusion nor a cynical rationalism,

but a capacity to play with illusions while never losing sight of the fact that

this is a form of play Consider the position of the child in relation to a

parent who, in one way or another, takes these kinds of illusions extremely

seriously, whose own sense of security in fact is contingent upon them. Such a

parent insists on specific overvaluations of the child or herself or both.

These illusions have become addictive for the parent, and they become a dominant

feature in the possibilities for relatedness which such a parent offers the

child. The more addictive the illusions for the parent, the more unavoidable

they become for the child, who feels that the only way to connect with the

parent, to be engaged with him, is to participate in his illusions. Such a

child must regard himself as perfect and extraordinary and be seen by the

parent that way, to be seen at all; or he must worship the parent as perfect

and extraordinary to become real and important to the parent. Further, children

tend to pick up how crucial such illusions are for the parent's shaky sense of self-esteem.

Deutsch (1937) long ago noted the role of parental "induction" in

cases of "folie-à-deux," where adoption by the child of the parent's

delusion represents "an important part of an attempt to rescue the object

through identification with it, or its delusional system" (p. 247).

Abandonment of parental illusions thus becomes an emotional equivalent of

abandonment of the parents themselves, the avoidance of which, as M. Friedman

(1985) has argued, is an underlying feature in many forms of psychopathology.

In such

circumstances, sustaining parental illusions becomes the basis for stability

and for maintaining connections with others, the vehicle for what Fairbairn

repeatedly terms the "tie to bad objects," or what Robbins (1982)

more recently has described as pathological efforts at symbiotic bonding. Here

illusions are no longer the spontaneously generated, transitory, playful

creation of an active mind. Illusions are insisted upon with utmost seriousness

by significant others, and they become the necessary price for contact and

relation. Ogden (1982) speaks of

<

the ever-present threat that if the infant fails to comply, he

would cease to exist for the mother. This threat is the muscle behind the

demand for compliance: "If you are not what I need you to be, you don't

exist for me." Or in other language, "I can see in you only what I

put there. If I don't see that, I see nothing.">> (p. 16)

This is true not

just of infancy, but throughout childhood and later into adulthood. Every

analyst is familiar with the dread adult patients frequently feel in connection

with major characterological change; they anticipate a profound sense of isolation

from parents (alive or dead) who related to them, seemed to need so much to

relate to them, only through their now-loosened and about-to-be-transcended

character pathology (see Searles, 1958).

The mithological

figure of Icarus vividly captures the powerful relationship between the child

and the parent's illusions. Daedalus, the builder of the Labyrinth, constructs

wings of feathers and wax, so that he and his son Icarus can escape their

island prison. The use of such wings requires a true sense of Nietzsche's dialectical

balance: flying too high risks a melting of the wings by the sun; flying too

low risks a weighing down of the wings from the dampness of the ocean. Icarus does

not heed the warning he receives. He flies too close to the sun; his wings

melt, and he plunges into the ocean, disappearing beneath a clump of floating

feathers.

We have all been

born of imperfect parents, with favorite illusions about themselves and their

progeny buoying their self-esteem, cherished along a continuum ending with

addiction to illusion. We have all come to know ourselves through participation

in parental illusions, which have become our own. Like Icarus, therefore, we

have all donned Daedalus' wings. It is the subtleties of parental involvement

with these illusions which greatly influence the nature of the flight provided by

those wings-whether one can fly high enough to enjoy them and truly soar, or

whether the sense of ponderous necessity concerning the illusions leads one to

fly too high or to never leave the ground.

The myth of

Icarus points to another significant feature of generational interaction in the

subtleties of narcissistic illusion. In most accounts Daedalus is portrayed as

a caring father, at least in his warnings to Icarus to fly neither too high nor

too low, and Daedalus himself is able to negotiate a successful flight to safety.

Children of illustrious parents are particularly prone to narcissistic

difficulties. With parents of distinction of one sort or another, it takes particular

sensitivity to be able to help a child sort through and digest parental

identifications to generate illusions and ambitions of his or her own.

In both prior

approaches to narcissism, pathological grandiosity and pathological

idealization are understood largely as forces operating within the internal

psychic economy of the individual. They are viewed as internally generated

phenomena, either as defensive solutions to anxiety, frustration, and envy, or

as spontaneously arising, pristine, early developmental needs. The developmental-arrest

approach suffers from this constraint just as much as the more traditional

approach. Illusion is treated not as a normal product of mental activity

throughout the life cycle, but is located within the earliest developmental

phases. And illusions within the psychoanalytic situation are treated as

reflective of the early developmental needs, in pure form, rather than as

learned modes of connection with others, as the not-at-all-playful,

stereotyped, compulsive patterns of integration they have become.

Ever since

Freud's abandonment of the theory of infantile seduction, the legacy of drive

theory for the subsequent history of psychoanalytic ideas has included an

underemphasis of the role of actual relationships in the evolution of mental

structures and content, and of the residues of actual interactions in fantasied

object ties. With respect to narcissism, both traditions isolate the figure

within the relational tapestry. In so doing, they overlook the extent to which

grandiosity and idealization function as interactional modes, arising as learned

patterns of integrating relationships, and maintained as the vehicle for

intimate connections (real and imagined) with others. They focus on one

dimension of the relational matrix, the self, but not on the self with others;

to regard these phenomena solely in terms of self-organization is like working

with only half the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

The major

theorists we have been considering do not completely fail to notice these

interactional facets of narcissistic phenomena. They are too astute as

clinicians to do so. The problem is that the specifics of parental character

and fantasied object ties do not fit into theoretical models emphasizing what

are taken to be spontaneously arising, developmental phenomena, so they are

noticed clinically and then passed over when major etiological dynamics are assigned

or technical approaches developed. The subtleties of the parents' personalities,

the ways in which they required the child to maintain narcissistic illusions,

are lost; the parents are viewed in a binary fashion, either as gratifying or

not gratifying infantile needs (drives or relational).

Freud's paper

"On Narcissism," for example, contains a wry and incisive description

of parents' narcissistic investment in their children:

“If we look at

the attitude of affectionate parents towards their children, we have to

recognize that 'it isa revival and reproduction of their own narcissism, which

they have long since abandoned… They are under a compulsion to ascribe every

perfection to the child - which sober observation would find no occasion to do -

and to conceal and forget all his shortcomings… They are inclined to suspend in

the child's favor the operation of all the cultural acquisitions which their own

narcissism has been forced to respect, and to renew on his behalf the claims to

privileges which were long ago given up by themselves… The child shall fulfill

those wishful dreams of the parents which they never carried out-the boy shall

become a great man and a hero in his father's place, and the girl shall marry a

prince as a tardy compensation for her mother. At the most touchy point in the narcissistic

system, the immortality of the ego, which is so hard pressed by reality, security

is achieved by taking refuge in the child. Parental love, which is so moving

and at bottom so childish, is nothing but the parents' narcissism born again.”

(1914b, pp. 90-91)

Freud calls our

attention to the striking similarity between the parents' attitude toward the

child and the child's attitude toward himself. The parent overvalues the child;

the child overvalues himself. Freud does not, however, derive the child's narcissism

from the parents' attitude! He points to the parents' often-compulsive need to

use the child as a magic solution for their own limitations and

disappointments. Yet he does not consider how such a set of parental

expectations and needs might contribute to the child's sense of who he is and

who he needs to be for others. Although parental values, internalized in the

ego ideal, become important later on in recapturing the primary narcissistic

experience, Freud derives infantile narcissism from the inherent properties of self-directed

libido. Infantile grandiosity is an instinctual vicissitude; self-love

generates narcissism, apart from the relational matrix. In effect, Freud

derives the parents' narcissism from the child's, their own unresolved infantile

narcissistic longings and the opportunity provided by their child's infantile

narcissism to evoke their own. In viewing narcissism as a quality inherent in

self-directed libido, Freud underplays the extent to which parental fantasies

influence the child's sense of who he is and has to be for the parents.

Infantile experience shapes adult character, and adult character through

parenting shapes infantile experience, in a continually evolving generational

cycle within the relational matrix. Kernberg similarly provides a vivid portrait

of parental narcissism at work in the dynamic interactions within families

producing children with later narcissistic difficulties.

Their histories reveal that each patient possessed some inherent quality which could have objectively aroused the envy or admiration ofothers. Forexample, unusual physical attractiveness or some special talent became a refuge against the basic feelings of being unloved and of being the objects of revengeful hatred. Sometimes it was rather the cold hostile mother's narcissistic use of the child which made him "special," set him off on the road in a search for compensatory admiration and greatness, and fostered the characterological defense of spiteful devaluation of others. For example, two patients were used by their mothers as a kind of "object of art," being dressed up and exposed to public admiration in an almost grotesque way, so that fantasies of power and greatness linked with exhibitionistic trends became central in their compensatory efforts against oral rage and envy. These patients often occupy a pivotal point in their family structure, such as being the only child, or the only "brilliant" child, or the one who is supposed to fulfill the family aspirations.(1975, pp. 234-235)

How could a

child growing up in such circumstances become anything but narcissistic? become

visible to his parents in any form other than as an extraordinary, larger-than-life

creature? Why the need to evoke a hypothetical excess of aggression (either

constitutional or based on great deprivation in the earliest years) to account

for what is more simply and clearly derivable from the relational matrix? Like

Freud, Kernberg sees the clinical relevance of parental values and

expectations, the constricted forms of relationships they offer to the child;

yet this factor is assigned only a peripheral etiological role in shaping later

defenses against early conflicts. Kernberg's model of mind, still drawing strongly

on the monadic framework of drive theory, regards pathological narcissism as an

internally generated mechanism, established in the first years of life in the

face of extreme oral rage. The mother is important, not in the subtleties of

her character and the particularities of the relational patterns she offers the

child, but in her gross role as frustrator of the child's oral needs and as an

object for the child's oral rage.

Kohut's clinical

reports reflect a similar striking discordance between rich observations of parent-child

interactions and a theoretical model of narcissism which assigns the particular

content of these interactions to a secondary role. Kohut describes patients who

exhibit various forms of grandiosity, some noisily proclaimed, others secretly

and shamefully harbored. Kohut considers these to be manifestations of

"archaic" grandiosity, which was not allowed to establish itself and

undergo normal transmuting internalization because of the parents' failures as

self-objects. Thus, his model derives narcissism from the expression of

inherent sources. Yet, Kohut often informs us (usually parenthetically) that

the parents failed the child in quite specific ways, using that child as a

narcissistic extension of themselves in precisely the manner in which the child

then constructs his grandiosity.

Within both

traditions there has been movement toward granting greater etiological

importance to parental character and the specifics of child-parent

interactions. From the drive-theory side, Rothstein (1984) has placed

increasing emphasis on the role of the actual relationship in the generation

and maintenance of narcissistic illusion, and Robbins (1982) has written of the

ways in which narcissistic phenomena operate as shared illusions, drawing on

grandiose fantasies of idealized objects. From the relational-model side, there

has been discussion of the parents, not simply in terms of their failure to provide

self-object functions for the child, but also in terms of their use of the

child as their own self-object (Atwood and Stolorow, 1984).

I have suggested

that in ideal parenting the parent participates with the child in a variable

fashion that contains both joyful play with illusions and an affirming embrace

of reality. Loewald has depicted the delicate interpenetrability between illusion

and consensual reality that can develop from such interactions in a redefinition

of the traditional concept of reality testing:

“Reality testing

is far more than an intellectual or cognitive function. It may be understood

more comprehensively as the experiential testing of fantasy - its potential and

suitability for actualization - and the testing of actuality - its potential

for encompassing it in, and penetrating it with, one's fantasy life. We deal

with the task of a reciprocal transposition.” (1974, p. 368)

How does the

analyst help the analysand arrive at such a balance between illusion and

reality, at the capacity to live in and fuse both realms? Loewald suggests that

the analyst's interpretations and demeanor convey a subtle double quality which

makes this possible. On the one hand, the analyst's descriptions and

interpretations enable the patient to advance his access to his own subjectivity

and inner resources. On the other hand,

“There may be at

times, in addition, that other quality to the analyst's communication, difficult

to describe, which mediates another dimension to the patient's experiences,

raising them to a higher, more comprehensively human level of integration and

validity while also signaling the transitory nature of human experience.”

(1974, p. 356)

Comentarii